The following is a discourse by Peter Ditzel from his on line Ministry called “Word of Grace” This discourse is posted on this site in its entirety, and without modification as required by permission by Peter Ditzel.

Ekklesia: The called out assembly

Peter’s website can be found by clicking this link: “Word of Grace”

I found this dissertation to be thorough in its research, objective and fair in presentation, and in harmony with the Bible and its teachings. It is for these reasons that I have chosen to post this article on this site; as the truth which is being presented to the children of God in these last days by our Lord and Saviour, is unfortunately being adulterated by lies from those who are lost, and have not yet come to know Jesus Christ.

I pray that you will take the time to read this document, and to visit Peter’s website.

Ekklēsia OR CHURCH, DOES IT MATTER?

PETER DITZEL

In the New Testaments of most English Bibles, the words “church” and “churches” appear a total of over one hundred times. (From now on, I will use “church” to stand for both the singular and plural.) With one exception in the King James Version (found in Acts 19:37), all of these instances of “church” are mistranslated from the Greek word ekklēsia. (Unless I am quoting a portion of Greek text, I will use the lexical form ekklēsia.) That’s right, I said mistranslated. Not only that, they are a deliberate mistranslation of ekklēsia. The fact that this mistranslation is so widespread and that it is deliberate should cause us to suspect that it is important to know what ekklēsia really means.

In this article, I am going to tell you the origins of the word “church” and its meaning, what ekklēsia means and how it was used in history and the Bible, what Jesus meant by His ekklēsia, why ekklēsia was deliberately mistranslated as “church”, and why all of this is important.

Church

It is generally agreed among etymologists who study the origins of words that our English word “church” comes from the Greek word kuriakos. This word is an adjective and it means belonging to or in some way related to the Lord.

The word kuriakos is found twice in the Bible. It is in 1 Corinthians 11:20, where it is translated as “Lord’s” in the term “the Lord’s supper.” And it is translated “Lord’s” in the term “Lord’s day” in Revelation 1:10.

So how did this adjective that means “Lord’s” come to be the origin of our English noun “church”? Words are funny things. They change over time.

The Online Etymological Dictionary

(Online Etymology Dictionary)

says that kuriakos “was used of houses of Christian worship since c.300.” Remember that date.

This was the time of Constantine the Great, who was emperor of the Roman Empire from A.D. 306 to 337. Up until this time, Christians were meeting in private houses. This brought the wrath of the Roman government upon them because, as Earle E. Cairns writes in Christianity Through the Centuries, “There could be no private religion…. The Christians held most of their meetings at night and in secret. To the Roman authority this could be nothing else than the hatching of a conspiracy against the safety of the state….

The secrecy of the meetings of the Christians also brought moral charges against them. Public rumor made them guilty of incest, cannibalism, and unnatural practices” (87).

The other religions of the Roman Empire had public meeting places, but the Christians met in private houses even though it brought persecution upon them. That’s right, meeting in private houses brought persecution upon the Christians. Contrary to what is often assumed, Christians did not meet in private houses to hide from persecution. They met in private houses by choice, and this choice made them subject to persecution.

But then Constantine (along with Licinius) granted religious tolerance in the Edict of Milan. Not only was Christianity now tolerated, but Constantine favored it, and began to build church buildings. He retained the idea that worship is public and expected Christians to follow that paradigm. “Constantine brought to Christianity a pagan notion of the sanctity of things and places” (Joan E. Taylor, Christians and the Holy Places, 308).

This erection of special buildings for Christian worship was part of what has been called the Constantinian shift that eventually, after Constantine’s death, led to the uniting of ‘church and state’ with the issuing of the Edict of Thessalonica.

This edict was released jointly by Theodosius I, Gratian, and Valentinian II. It made the faith “which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria [the bishops of Rome and Alexandria]” the official religion of the people under those emperors. It further said, “We authorize the followers of this law to assume the title of ‘Catholic Christians’; but as for the others, since, in our judgment they are foolish madmen, we decree that they shall be branded with the ignominious name of ‘heretics’, and shall not presume to give to their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of the divine condemnation, and in the second the punishment of our authority which in accordance with the will of Heaven we shall decide to inflict.”

So, now the tables were turned—the persecuted were now the persecutors. Or perhaps the tables were not turned. Maybe the pagans were still running things, but now under the new name of Christianity, or, as they put it themselves, ‘Catholic Christianity’.

Notice a couple of the words used in the edict. “Conventicles” are private meetings not sanctioned by law. The Latin word from which this is translated in the edict is conciliabula. It has a similar meaning to the English “conventicles.” So, this edict outlawed the meetings Christians had been having in their houses all along. The English translation of the edict also uses the word “churches.” But the Latin word from which this was translated is ecclesiarum, a Latin derivative of ekklēsia. So, those who did not accept the bishops of Rome and Alexandria were not to call their meetings ekklēsia.

It should not be supposed that everyone fell into line. Leonard Verduin writes, “Thus, before the Constantinian change had come full circle, the death sentence had been prescribed for either holding or attending a conventicle” (The Anatomy of A Hybrid, 99). And it is well documented that the faithful who would not give in to the institutionalized state church continued to meet privately and illegally for centuries. Of these secret assemblies, Verduin writes in another of his books that “one of the things required of a convert…was the promise not to go again into a stone-pile, a cumulus lapidum,” as they called church buildings (The Reformers and Their Stepchildren, 167).

But, for the followers of these bishops, the people who were to now be called Catholic Christians, there were official church buildings. And these buildings, as I have pointed out, were called kuriakos, “the Lord’s.” This was just a shortened way of expressing the idea these people had that these buildings were the Lord’s house or kuriakē oikia. For, continuing with pagan notions Constantine had retained, they considered the buildings themselves to be sacred. Thus, a kuriakos, or church, was a sacred building.

Before continuing, I want to ask these questions: Was the ekklēsia that Jesus built a sacred building He built as the son of a carpenter, or was it the people He called as the Son of God?

Over the years, the word “church” evolved to take on other meanings. Rather than go through a lengthy history, I will demonstrate the fact of these other meanings by simply quoting the dictionary definitions from two highly respected dictionaries, one American and the other British.

Merriam-Webster’s 11th Collegiate Dictionary defines “church” as follows:

1 : a building for public and especially Christian worship

2 : the clergy or officialdom of a religious body

3 : often capitalized : a body or organization of religious believers: as a : the whole body of Christians b DENOMINATION <the Presbyterian church> c : CONGREGATION

4 : a public divine worship <goes to church every Sunday>

5 : the clerical profession <considered the church as a possible career>

Collins English Dictionary has this definition for “church”:

1 a building designed for public forms of worship, esp Christian worship

2 an occasion of public worship

3 the clergy as distinguished from the laity

4 (usually capital) institutionalized forms of religion as a political or social force: conflict between Church and State

5 (usually capital) the collective body of all Christians

6 (often capital) a particular Christian denomination or group of Christian believers

7 (often capital) the Christian religion

8 (in Britain) the practices or doctrines of the Church of England and similar denominations

Notice that many of these definitions are in some way related to buildings, public worship, clergy, and institutionalized religion. None of these things are related to the biblical meaning of ekklēsia. They have nothing to do with the ekklēsia Jesus built.

Etymology of Ekklēsia and Use in History

The word ekklēsia is found in 116 places in the New Testament. In most English Bibles, it is translated as “church” in all of those places except three. In Acts 19:32 and 41, it is translated as “assembly” and refers to the people whom Demetrius had called together (see Acts 19:25),

“Whom he called together with the workmen of like occupation, and said, Sirs, ye know that by this craft we have our wealth”. Acts 19:25.

and in verse 39 it is also translated “assembly” and refers to a lawful assembly.

“But if ye enquire any thing concerning other matters, it shall be determined in a lawful assembly.” Acts 19:39.

Ekklēsia is a compound word. The first part is ek. It is a preposition that means “out of,” “out from,” or “from.” The second part of ekklēsia—klēsia—is a derivative of the Greek word kaleō. Kaleō is a verb that means “to call.” So, ekklēsia is a compound of a preposition and a verb, but ekklēsia itself is a noun. In its most basic form, ekklēsia means “the called out from” or “those called out from.” In other words, it refers to people called out from or out of something.

In ancient Greece, ekklēsia came to be used for the people who were called out of the community to the assembly. The Encyclopedia Britannica says,

Ecclesia, Greek Ekklēsia, (“gathering of those summoned”), in ancient Greece, assembly of citizens in a city-state. Its roots lay in the Homeric agora, the meeting of the people. The Athenian Ecclesia, for which exists the most detailed record, was already functioning in Draco’s day (c. 621 bc). In the course of Solon’s codification of the law (c. 594 bc), the Ecclesia became coterminous with the body of male citizens 18 years of age or over and had final control over policy, including the right to hear appeals in the hēliaia (public court), take part in the election of archons (chief magistrates), and confer special privileges on individuals. In the Athens of the 5th and 4th centuries bc, the prytaneis, a committee of the Boule (council), summoned the Ecclesia both for regular meetings, held four times in each 10th of the year, and for special sessions. Aside from confirmation of magistrates, consideration of ways and means and similar fixed procedures, the agenda was fixed by the prytaneis. Since motions had to originate in the Boule, the Ecclesia could not initiate new business. After discussion open to all members, a vote was taken, usually by show of hands, a simple majority determining the result in most cases. Assemblies of this sort existed in most Greek city-states, continuing to function throughout the Hellenistic and Roman periods, though under the Roman Empire their powers gradually atrophied.”

(http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/177746/Ecclesia)

Many people make the mistake of saying that ekklēsia merely means an assembly. This is a commendable start and is worlds better than “church,” but they forget that it means an assembly that has been called out from something. In ancient Greece, it was the assembly called out or summoned from the community.

Ekklēsia in the Septuagint

Ekklēsia was sometimes used by the translators of the Greek translation of the Old Testament called the Septuagint (abbreviated LXX). Ekklēsia is often used for the assembly or congregation of Israel, as well as for other types of assemblies. The first appearance of the word in the LXX is in Deuteronomy 9:10 where it is translated “assembly”:

“And the LORD delivered unto me two tables of stone written with the finger of God; and on them was written according to all the words, which the LORD spake with you in the mount out of the midst of the fire in the day of the assembly.”

Something to keep in mind is that the children of Israel came out of Egypt and were summoned or called to be an assembly before God. The historical Greek use of ekklēsia, as well as its use in the LXX—which was the version of the Scriptures commonly used in the time of Jesus and the apostles—can help us understand what Jesus had in mind when He chose to use this word. By the way, in Acts 7:38, Stephen also uses ekklēsia when speaking of the assembly of Israel at Mount Sinai.

“This is he, that was in the church in the wilderness with the angel which spake to him in the mount Sina, and with our fathers: who received the lively oracles to give unto us:” Act 7:38.

Ekklēsia in the New Testament

The first place in the New Testament that we find the word ekklēsia is in Matthew 16:18, where Jesus says,

“And I say also unto thee, That thou art Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church; and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” Matthew 16:18.

I have already discussed the Peter/rock aspect of this verse here (http://www.wordofhisgrace.org/rock.htm).

Now I simply want to point out that the first place ekklēsia is mentioned in the New Testament is here where Jesus said He would build (oikodomēsō—really “house-build” but, of course, here with a spiritual meaning) His ekklēsia.

We have seen that the most basic meaning of ekklēsia is “those called out from.” We have also seen that the ancient Greeks used this word to refer to the people called out from their community to the assembly. And we have seen that the translators of the LXX often used ekklēsia to refer to the Israelites who were called out of Egypt and assembled before God at Sinai.

Now, let’s see if there are parallels to these meanings in the New Testament.

In Jesus’ allegory of the Good Shepherd and the sheepfold (see John 10), He says,

“To him [the Shepherd] the porter openeth; and the sheep hear his voice: and he calleth his own sheep by name, and leadeth them out” (verse 3).

“Calleth” is from kaleō. If you read this entire allegory, you will see that it pictures Jesus calling those Jews who are His, and leading them out of the sheepfold. Notice that He is both the Shepherd who leads, and the Door—the way out of the fold.

The fold is national Israel and it’s religion that keeps them separate from any other sheep. The Shepherd puts them, along with His other sheep—His people in other nations—into one flock together. These Jews and Gentiles together are His ekklēsia.

“But ye are a chosen generation, a royal priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people; that ye should shew forth the praises of him who hath called you out of darkness into his marvellous light” (1 Peter 2:9).

“Called” is from kaleō and “out of” is from ek, the two words that create the word ekklēsia. Here, we see that we are called out of darkness and into God’s light.

In Galatians 5:13, Paul writes,

“For, brethren, ye have been called unto liberty; only use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one another.” Galatians 5:13

“Called” is from kaleō. The context of this verse shows that what we have been called from is bondage to the law (see, for example, verses 1-4 of this chapter), and the verse itself tells us we have been called to liberty or freedom from this bondage.

Peter writes,

“But the God of all grace, who hath called us unto his eternal glory by Christ Jesus, after that ye have suffered a while, make you perfect, stablish, strengthen, settle you” (1 Peter 5:10).

“Who hath called” is translated from kaleō. The word “by” in the King James Version is actually en, which is “in.” So, God has called us to his eternal glory in Jesus Christ.

Notice something: The Israelites were called from the bondage of Egypt to a physical manifestation of God’s glory at Mount Sinai. But they were also called to the law, which is another kind of bondage (Galatians 4:24). On the other hand, we have been called out of darkness, out of the world, out of sin, out of bondage to the law and to God’s glory in Jesus Christ and to liberty.

We are called to both God’s glory, and liberty in Jesus Christ (notice Galatians 2:4; 5:1).

“And that because of false brethren unawares brought in, who came in privily to spy out our liberty which we have in Christ Jesus, that they might bring us into bondage:” Galatians 2:4.

“Stand fast therefore in the liberty wherewith Christ hath made us free, and be not entangled again with the yoke of bondage.” Galatians 5:1.

The Israelites were called to Mount Sinai; we have been called to the Jerusalem above which is free (Galatians 4:26);

“But Jerusalem which is above is free, which is the mother of us all.” Galatians 4:26.

or, put another way,

“18 For ye are not come unto the mount that might be touched, and that burned with fire, nor unto blackness, and darkness, and tempest,

19 And the sound of a trumpet, and the voice of words; which voice they that heard intreated that the word should not be spoken to them any more:

20 (For they could not endure that which was commanded, And if so much as a beast touch the mountain, it shall be stoned, or thrust through with a dart:

21 And so terrible was the sight, that Moses said, I exceedingly fear and quake:)

22 But ye are come unto mount Sion, and unto the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to an innumerable company of angels,

23 To the general assembly and church of the firstborn, which are written in heaven, and to God the Judge of all, and to the spirits of just men made perfect,

24 And to Jesus the mediator of the new covenant, and to the blood of sprinkling, that speaketh better things than that of Abel.” Hebrews 12:18-24.

When we read this, we should understand that Hebrews was written to the Jewish Christians who were having trouble understanding the shift God had made from dealing with the Jews under the law, to dealing with Jews and Gentiles under the grace of the New Covenant.

So, the writer tells them that now that they are Christians, they have not come to Mount Sinai, representing the law, but to Mount Zion and the heavenly Jerusalem and to myriads of angels.

He then says they have come “to the general assembly and church of the firstborn.” “General assembly” and “church” are two words for the same thing. “Church” is ekklēsia. But the writer wants these Jews to understand the same thing Jesus teaches in His allegory in John 10. The ekklēsia is no longer the called out assembly of Jews receiving the law at Mount Sinai. The ekklēsia is now the called out Jews and Gentiles receiving liberty at Mount Zion and the heavenly Jerusalem.

And so, he also calls the ekklēsia the “general assembly,” the panēgurei. This, too, is a compound of two words: pan, meaning “all” or “the whole” or “entire” and agora, which means “a gathering” or “an assembly” (it also came to mean the town square or marketplace, since this is where the gatherings were held). Panēgurei even came to mean a festal gathering or assembly, probably because such festivals included people of all sorts.

So, the writer is saying to the Jewish Christians, you have not come to some nationally exclusive assembly (the way it was under the Old Covenant). You have come to the entire gathering or festal assembly that is the ekklēsia, God’s people from all nations called out of darkness and bondage and gathered in freedom before God.

Ekklēsia Not Only Local

I should hope that the exciting and inspiring Scriptures we have just examined would cause us to see the big picture of the ekklēsia. Its primary use in the New Testament shows it to be inclusive of all nationalities of people and a spiritual, even a festal, gathering in liberty and light before God. The ekklēsia that Jesus built is composed of all believers, it is not limited to location, and it is not limited by time—all believers everywhere are always assembled before God.

Nevertheless, apparently not wanting to be bothered with the facts, many people try to make a point that the ekklēsia is only local. There are entire denominations, such as Landmark Baptists, who consider the doctrine of the “local church only” to be pivotal. But, besides those we have already seen, look at just a few of the Scriptures that cannot be referring to only local churches:

“And hath put all things under his feet, and gave him to be the head over all things to the church” (Ephesians 1:22),

“To the intent that now unto the principalities and powers in heavenly places might be known by the church the manifold wisdom of God…. Unto him be glory in the church by Christ Jesus throughout all ages, world without end. Amen” (Ephesians 3:10, 21),

“For the husband is the head of the wife, even as Christ is the head of the church: and he is the saviour of the body. Therefore as the church is subject unto Christ, so let the wives be to their own husbands in every thing. Husbands, love your wives, even as Christ also loved the church, and gave himself for it…That he might present it to himself a glorious church, not having spot, or wrinkle, or any such thing; but that it should be holy and without blemish…. For no man ever yet hated his own flesh; but nourisheth and cherisheth it, even as the Lord the church…. This is a great mystery: but I speak concerning Christ and the church” (Ephesians 5:23-25, 27, 29, 32),

“And he is the head of the body, the church: who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence…. Who now rejoice in my sufferings for you, and fill up that which is behind of the afflictions of Christ in my flesh for his body’s sake, which is the church” (Colossians 1:18, 24).

Concerning Matthew 16:18, Landmark Baptists usually take either one of two positions:

1. Jesus said He would build His churches, OR

2. Jesus was referring to the Jerusalem church.

My answer to the first is that the specific word ekklēsian in this verse is singular.

My answer to the second is that, if true, it would make Jesus the builder of only one local church. Does this also mean that Jesus was the head of only one local church, and died for only one local church?

How patently absurd.

Jesus was familiar with all of the LXX Scriptures, not just the ones concerning the ekklēsia at Sinai. The word choices in the following verses are particularly interesting:

“Thy seed will I establish for ever, and build up thy throne to all generations. Selah. And the heavens shall praise thy wonders, O LORD: thy faithfulness also in the congregation of the saints” (Psalm 89:4-5).

In the LXX, “build up” is oikodomēsō (house build) and “congregation” is ekklēsia.

“My praise shall be of thee in the great congregation: I will pay my vows before them that fear him” (Psalm 22:25)

—see also Psalm 22:22 and Hebrews 2:12). In the LXX, “great congregation” is ekklēsia megalē. Read the context, and you will see that these are the prophetic words of Jesus Christ. Ekklēsia megalē is singular.

Further, in 1 Peter 1:1, we see that Peter wrote his epistle to five different locations. Yet, in 1 Peter 2:5, Peter wrote, “Ye also, as lively stones, are built up [oikodomeisthe—”house built”] a spiritual house, an holy priesthood, to offer up spiritual sacrifices, acceptable to God by Jesus Christ.” “A spiritual house” is singular.

Local Manifestations of the Ekklēsia

Although there are many Scriptures that speak of the ekklēsia as all Christian believers, and that is certainly the primary meaning, there are also Scriptures that use the word ekklēsia to speak of only a portion of the whole ekklēsia. Thus, we have the

“church which was at Jerusalem,” (Acts 8:1),

“the church that was at Antioch” (Acts 13:1),

“the church which is at Cenchrea” (Romans 16:1),

“the church of God which is at Corinth” (1 Corinthians 1:2),

and so on, including the seven churches in Revelation 2 and 3.

Now notice the specific setting for these local manifestations of the ekklēsia:

“Likewise greet the church that is in their house…,” (Romans 16:5),

“Aquila and Priscilla salute you much in the Lord, with the church that is in their house…,” (1 Corinthians 16:19),

“Salute the brethren which are in Laodicea, and Nymphas, and the church which is in his house…,” (Colossians 4:15),

“And to our beloved Apphia, and Archippus our fellowsoldier, and to the church in thy house” (Philemon 1:2).

Notice also Acts 8:3:

“As for Saul, he made havock of the church, entering into every house, and haling men and women committed them to prison.” Acts 8:3.

Saul made havoc of the ekklēsia by entering into every house. Obviously, he was finding the ekklēsia in houses.

I want to point out that none of these Scriptures so far clearly refers to local meetings of the ekklēsia. References to a portion of the ekklēsia in a city or in a house do not necessarily imply meetings. Therefore, let’s look at more Scriptures.

So far, we have seen ekklēsia used for all the people of God who are always an assembly before God, a portion of those people in a city or other region, and those same people in houses or families (the Greek word oikos means either house or family). Now, in 1 Corinthians 11:18, we see ekklēsia used in a somewhat different way:

“For first of all, when ye come together in the church, I hear that there be divisions among you; and I partly believe it.”

Here we see ekklēsia used for an actual meeting. This tells us that while we are always the ekklēsia gathered before God, there are times when we have local meetings. Certainly, there are other Scriptures, such as Acts 2:42, 46; 1 Corinthians 11 and 14; and 1 Timothy 2 that are references to meetings or instructions for meetings of the ekklēsia.

Translation Instructions

We have now seen that the ekklēsia built by Jesus Christ and found throughout the New Testament is the body of Christian believers who have been called out of darkness and bondage to the assembly in light and freedom before God. We have also seen that “church” comes from kuriakos, a completely different Greek word. Kuriakos referred to a building set apart as sacred and, thus, considered to be the Lord’s. Although some have tried to read the meaning of ekklēsia back into the word “church,” “church” is still intimately associated in most people’s minds with buildings, public worship, institutionalized religion, and the clergy of that institutionalized religion.

From the time of Constantine, the state-sanctioned Christians met in special, sacred, public buildings.

Over time, these buildings became intimately wrapped up in people’s minds with the institution and its clergy. Thus, even in languages that retained a form of the word ekklēsia, its meaning became corrupted from that in the Bible to the definition of “church.” And in languages that used the word “church,” that word never really took on the meaning of ekklēsia.

This was unfortunate as it gave even people who had access to some of the early Bibles in their native language a false idea of what Jesus built. Instead of the people God called out of darkness and bondage to His assembly in light and freedom, they thought of buildings and institutions and clergy.

This was the situation in England both before and even after its break from Rome. But neither the clergy nor the king considered this any pity since it bolstered their state-church power and kept the people ignorant and happy. This state of bliss was upset when William Tyndale made a new and unofficial translation of the Bible into English.

Tyndale, realizing that “church” was not a proper translation of ekklēsia rendered it “congregation.” Although King Henry VIII at first outlawed Tyndale’s translations; being the unpredictable figure that he was, he later approved the Great Bible that was largely Tyndale’s translation work.

During the reign and persecutions of the Catholic Queen Mary, many English Protestant scholars went to Geneva, where they produced the Geneva Bible. Interestingly, being produced in the church-state of Geneva, the Geneva Bible returned to translating ekklēsia as “church.” But when Elizabeth I came to the throne, she found the Calvinist marginal notes in the Geneva Bible offensive, so she ordered another translation. The result was the Anglo-Catholic Bishop’s Bible. This Bible, of course, also translated ekklēsia as “church” in most instances but used “congregation” in Matthew 16:18 (go figure!).

When King James VI of Scotland became King James I of England, he also became the head of the Church of England (as had, and do all English monarchs since King Henry VIII). James was not happy that the Reformation had not just brought about new state churches in Europe, but had also stirred up some people to want a purer church in England, one that did not have so many of the trappings of Catholicism. He considered these people—some of the Presbyterians in Scotland, and Puritans, Separatists, and other non-conformists in England—to be troublemakers. On the other hand, although the Church of England was a hybrid of Catholicism and Protestantism, James also had no love for Catholics, especially after the discovery of the Gunpowder Plot, a failed assassination attempt by a group of English Catholics. His response was to try to unite his church under yet another translation of the Bible, one that would be a compromise between the more Protestant Bibles and the Bishop’s Bible.

At the Hampton Court Conference of 1604, in which he proposed the new Bible, the King showed that he had no qualms about stacking the deck. Among his comments, he said, “…we acknowledge the government ecclesiastical, as it now is, to have been approved by manifold blessings from God himself…. I approve the calling and use of Bishops in the Church, and it is my aphorism, ‘No Bishop, no King’…. I will have one doctrine, one discipline, one religion, in substance and in ceremony…. If you aim at a Scottish presbytery, it agrees as well with monarchy as God and the devil. Then Jack, and Tom, and Will, and Dick, shall meet and censure me and my Council…. If this be all your [Puritan] party has to say, I will make them conform themselves, or else I will harry them out of the land, or else do worse.”

The result was that the king, and Richard Bancroft the Bishop (and later Archbishop) of London, issued a set of rules to the translators. Among them was a rule that ordered that the text of the Bishops Bible would be the primary guide for the translators, and that, if the Bishops Bible was deemed problematic in any situation, the translators were then permitted to consult these other translations: the Tyndale Bible, the Coverdale Bible, Matthew’s Bible, the Great Bible, and the Geneva Bible.

Another rule was, “The old ecclesiastical words to be kept, viz, the word Church not to be translated Congregation, & c.”

And so my case is proved that not only is the word “church” a wrong translation of ekklēsia, it is a purposeful mistranslation of ekklēsia. And not only is it a purposeful mistranslation, it is a purposeful mistranslation designed to mislead the people into following the established church, and away from any ideas they may have been developing about the true understanding of the ‘called out assembly’.

Why This Is Important

We must not make the mistake of thinking that all of this is just a small matter. In John 6:63, Jesus said,

“It is the spirit that quickeneth; the flesh profiteth nothing: the words that I speak unto you, they are spirit, and they are life.”

Peter agreed that Jesus had the words of eternal life (verse 68). The words are spirit and life. That sounds vitally important to me. Revelation 22:19 says,

“And if any man shall take away from the words of the book of this prophecy, God shall take away his part out of the book of life, and out of the holy city, and from the things which are written in this book.”

One way to take words from a book is to change their meaning. Jesus also said,

“For whosoever shall be ashamed of me and of my words, of him shall the Son of man be ashamed, when he shall come in his own glory, and in his Father’s, and of the holy angels” (Luke 9:26),

and,

“He that rejecteth me, and receiveth not my words, hath one that judgeth him: the word that I have spoken, the same shall judge him in the last day” (John 12:48).

Are we going to be faithful to Jesus’ words or are we not? Notice this:

“If a man love me, he will keep my words: and my Father will love him, and we will come unto him, and make our abode with him” (John 14:23).

When we change the meaning of a word that God intended in a Scripture, whether we substitute a different word or not, we have changed the word.

Meanings are important. For example, in many languages, ekklēsia has merely been transliterated. In Latin, ekklēsia is ecclesia. In Spanish, ekklēsia has become iglesia. In French, it is église. But, as I briefly mentioned earlier, the meaning of these words is no longer that of the Greek word ekklēsia that is found in the New Testament.

These transliterations have come to mean the special building for worship services, the organization that owns it, and the clergy that have authority and perform the service. In these cases, although the word ekklēsia has been preserved in form, it has lost its original meaning and is, thus, misleading.

The meaning has been lost. I am concerned about preserving the original meaning of the word, which, after all, was the intent of the Holy Spirit.

In English (as in other languages such as German that use derivatives of kuriakos), “church” is a totally misleading translation of ekklēsia. “Church” originally meant a building set apart as sacred and, thus, considered to be the Lord’s.

This is a concept that is totally foreign to the New Covenant. Under the New Covenant, there are no sacred places (John 4:21, 23; Acts 7:48-49). “Church” eventually evolved even further from the New Testament meaning of ekklēsia by coming to also encompass priests holding an office (a concept that came to be called the clergy—also a notion foreign to the New Covenant) and the denomination or institution that they formed.

Only in relatively recent history have some people tried to work into the word “church” the meaning of ekklēsia. But “church” has so many other connotations in people’s minds that this is really a hopeless cause to try to make it mean ekklēsia.

One might wonder if all I am saying here is all a hopeless cause anyway. After all, the word “church” and the baggage it carries is so ingrained into people’s minds that how can we hope to make a change?

It is daunting, I will admit. But, if the Lord is willing and He is strengthening us, we can make a difference. If you believe what this article says about ekklēsia and you did not know this before, then this article has not been in vain.

As you read your English Bible, you can at least begin to substitute in your mind “called out assembly” for “church.” If you do this, I can almost guarantee that having a correct understanding of this one biblical word will, over time, change your thinking about “church” and many other Bible doctrines. You will also want to spread the word to others. You may even want to get one of the few English translations that renders ekklēsia as “assembly.” Some are listed at the end of this article.* You may even take the big plunge and start to learn biblical Greek.

Who knows, eventually there may be enough of us that the big publishers will publish Bibles with a correct translation of ekklēsia. I am not, by the way, saying that ekklēsia is the only word that is so blatantly mistranslated. There are others, and, Lord willing, I will mention them in future articles.

Something else we can do—pray.

Jesus said,

“If ye abide in me, and my words abide in you, ye shall ask what ye will, and it shall be done unto you” (John 15:7).

No, I do not think it is a hopeless cause. God’s Word will be preserved.

“Heaven and earth shall pass away: but my words shall not pass away.” Mark 13:31

* The following Bibles translate ekklēsia as “assembly.” The listing of these Bibles should not be taken as my endorsement of them. I have posted links to online information about these Bibles at the bottom of this page: http://www.wordofhisgrace.org/ekklesia3.htm

Analytical-Literal Translation of the New Testament: Third Edition (link goes to Amazon.com)

Apostolic Bible Polyglot (link goes to publisher’s website)

KJ3 Literal Translation New Testament (link goes to Amazon.com)

Modern Young’s Literal Translation New Testament (link goes to Amazon.com)

A Non-Ecclesiastical New Testament (link is an Adobe Acrobat file of the entire New Testament—Note, I am unfamiliar with the website that hosts this link.)

Tyndale’s New Testament (link goes to a free online version of Tyndale’s New Testament)

Young’s Literal Translation of the Bible (link goes to Amazon.com)

In Chapter Four of Love Wins, Bell criticizes some statements of faith that he has taken from evangelical church websites that reflect Jesus’ teachings on Hell: “The unsaved will be separated forever from God in hell.” After giving a number of examples with which he feels uncomfortable, Bells states,

In Chapter Four of Love Wins, Bell criticizes some statements of faith that he has taken from evangelical church websites that reflect Jesus’ teachings on Hell: “The unsaved will be separated forever from God in hell.” After giving a number of examples with which he feels uncomfortable, Bells states,  The emergent-friendly, Global Dictionary of Theology, makes a distinction between ‘Hopeful Universalism’ and ‘Convinced Universalism’:

The emergent-friendly, Global Dictionary of Theology, makes a distinction between ‘Hopeful Universalism’ and ‘Convinced Universalism’: Indeed, in the very preface of Love Wins, Bell contradicts Jesus’ teaching that few would actually be saved. Bell writes:

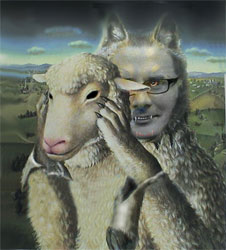

Indeed, in the very preface of Love Wins, Bell contradicts Jesus’ teaching that few would actually be saved. Bell writes: It is a sobering thought that Jesus went on to state in the verses immediately following His teaching on the narrow and broad roads, that false prophets would come in sheep’s clothing (Matthew 7:15-21). Such false prophets stand at the cross roads between the broad and narrow road, claiming to represent Christ, while pointing their followers toward the broad road that leads destruction, assuring them that it eventually leads to Heaven. Consider this for a minute. Isn’t this exactly what Rob Bell is doing?

It is a sobering thought that Jesus went on to state in the verses immediately following His teaching on the narrow and broad roads, that false prophets would come in sheep’s clothing (Matthew 7:15-21). Such false prophets stand at the cross roads between the broad and narrow road, claiming to represent Christ, while pointing their followers toward the broad road that leads destruction, assuring them that it eventually leads to Heaven. Consider this for a minute. Isn’t this exactly what Rob Bell is doing? Rob Bell not only redefines Hell by teaching that it will only be a temporary abode for those who want to leave later, but he redefines Hell by claiming that it is not so much about the after life, but it’s about what you make of the life here and now. In his book, Velvet Elvis, Bell had already stated this position:

Rob Bell not only redefines Hell by teaching that it will only be a temporary abode for those who want to leave later, but he redefines Hell by claiming that it is not so much about the after life, but it’s about what you make of the life here and now. In his book, Velvet Elvis, Bell had already stated this position: Rob Bell takes every possible liberty to deny reality and to either explain Hell away or get everyone into Heaven, regardless of his or her rejection of God and the Gospel. Bell not only empties Hell of God’s holy wrath, he creates an exit door from the inside out and claims that Hell is merely what we make it. He also claims that most of the imagery of future judgments in Hell were fulfilled on earth in AD 70 (p. 81).

Rob Bell takes every possible liberty to deny reality and to either explain Hell away or get everyone into Heaven, regardless of his or her rejection of God and the Gospel. Bell not only empties Hell of God’s holy wrath, he creates an exit door from the inside out and claims that Hell is merely what we make it. He also claims that most of the imagery of future judgments in Hell were fulfilled on earth in AD 70 (p. 81). By claiming that the unrepentant wicked will have a chance to get to Heaven from Hell, Rob Bell has gone beyond that of Edward W. Fudge, who states in The Fire That Consumes,

By claiming that the unrepentant wicked will have a chance to get to Heaven from Hell, Rob Bell has gone beyond that of Edward W. Fudge, who states in The Fire That Consumes,  Biblical Scholar D.A. Carson, commenting on Matthew 25:46, says :

Biblical Scholar D.A. Carson, commenting on Matthew 25:46, says : “What is hard to prove, but seems to me probable, is that one reason why the conscious punishment of hell is ongoing is because sin is ongoing.”

“What is hard to prove, but seems to me probable, is that one reason why the conscious punishment of hell is ongoing is because sin is ongoing.” There is hardly any wiggle room for a second chance in hell in these passages or anywhere in Scripture. Bell would have his readers believe of the book of Revelation that

There is hardly any wiggle room for a second chance in hell in these passages or anywhere in Scripture. Bell would have his readers believe of the book of Revelation that  May God give us the grace, in these times of apostasy, to hold fast to Jesus’ teachings and remain faithful to our loving and Holy Lord to the end. May God deliver His bride from the cotton candy Christianity that is endemic in Emergent Churches and among false prophets who lead the lost into believing they can put off repentance until after death.

May God give us the grace, in these times of apostasy, to hold fast to Jesus’ teachings and remain faithful to our loving and Holy Lord to the end. May God deliver His bride from the cotton candy Christianity that is endemic in Emergent Churches and among false prophets who lead the lost into believing they can put off repentance until after death.